“In the preparation of this book, two important guidelines have been followed. First, the decision was made to present the material, for the most part, as a gradual, year-by-year unfolding of events, rather than as a hindsight overview. Very often, the historical overview approach transforms events of the past into smoothly flowing happenings, which seem to have followed a script in a straight-forward, linear fashion. As a result, life during earlier periods appears to have been immensely simpler and clearer, more one-dimensional, than that which we experience today. The very fact that historians generally know the outcome of the activities about which they write often eliminates the drama and uncertainty from their discussion of those events. To retain these human elements in the present work, the author has very often refrained from relating the result of a given series of activities following the presentation and discussion of those activities. This approach allows the reader to better absorb the various sensations and concerns which resulted at the time, caused by not knowing all of the facts and not being able to discern the future; these are feelings which are central to all human experiences.

Certain readers will find this style of presentation a little disconcerting, particularly since the text does not offer a steady, flowing thread of narrative. Instead, it allows the myriad elements of the story to unfold in irregular fits and starts, with many related and unrelated side events emerging at intervals to clutter the scene. This approach presents the complex and sometimes contradictory array of events which made up real life during the period under study. It is not the clear, omniscient summation based upon hindsight which is so often presented as history. On the other hand, the content of this book is not a simple chronological gathering of period documents, presented in undigested form. Rather, it contains a judicious balance of period material and historical analysis, allowing the reader to both relish the gradual unfolding of events and also gain an understanding of the final results of those events.

The second decision which was made concerning this book was to use it as a vehicle which would present large numbers of original French documents from the period, either in their entirety or as extensive quoted extracts. This was done for a number of reasons. First of all, most readers, including both Anglophones and Francophones, do not have ready access to early French documents. Most of these records lie in vast stores of microfilm within various archives in Canada and France.

A hurdle even more formidable than access to ancient French records is the deciphering of their handwritten texts. After documents appropriate to one’s area of study have been located in the microfilm repositories, and paper copies have been produced from the microfilm copies of the originals, the greatest challenge still remains. That challenge is deciphering and converting into typewritten text the often scrawled writings from several centuries ago. A large percentage of the documents were written by various notaries in legal terminology, intended only as records to which each given notary would refer back, in case of later disagreements, or when a contract was fulfilled and was paid off or cancelled. In these instances, the records were intended only for the eyes of the particular notary who jotted them down, as was also the case with outfitters’ ledgers. This single-user practice often led to handwriting which was far less than clear and concise. Other problems which are involved in deciphering the various documents are the ideosyncracies of penmanship of each individual writer, the many abbreviations which were used, the widely varying phonetic spellings of the time, and even the splotches of ink which typically soaked through the paper from the writing on the opposite side of the page. Thus, when dealing with most of the original French records, the greatest hurdle is the transcription, rather than the translation, of the text.

Having made that point, however, one must also note that various translations of early documents relating to New France are often less than correct and communicative. First of all, the translator must be familiar with the legalese, the abbreviations, and the phonetic spellings of the period, in order to produce a translation which is more than a “word salad,” or a legal document that is more than an awkwardly worded, single sentence or paragraph which extends for a full page or more. Just as importantly, the translator must be completely familiar with all of the objects of daily life of the period, and the specific names which those objects were called at that time. This is absolutely crucial when translating such documents as inventories of possessions, or rosters of trade merchandise, missionary supplies, or military stores…

…Recovering and gathering together a huge array of pieces of evidence from the past, and then assembling them into a comprehensible whole, has been the guiding purpose of this work. When attempting to make sense of early historical events, original documents and excavated artifacts from the period assist by providing considerable amounts of information. Offering the actual words of the early texts, rather than summarizing their contents, is crucial to the author’s goals. First of all, the original documents hold the attention of the reader much more strongly than do modern summations. More importantly, the documents provide many more small details concerning life in earlier times, and supply much more flavor relating to the issues and concerns of the day. These multiple layers of information assist in filling in the picture of a great many of the minor and less clearly understood events of the era, which took place between and around the more widely known happenings that typically appear in written histories. Period documents show that life was not nearly so neat and uncomplicated as historical summaries usually present. For these reasons, myriad original texts have been included within the main narrative of this book, rather than buried in the Appendix at the back. Their location in the main body of material underscores their value in transmitting volumes of pertinent information.”

“The historical approach of the present study is generally one of microvision, focusing in many cases upon numerous specific individuals and the details of their lives, rather than one of macrovision, which views events in a more global manner, in relation to world politics and economics. The more personalized version of history which is explored here deals with individual traders, voyageurs, investors, outfitters, translators, blacksmiths, military officers, and native leaders, as well as the specific individuals with whom they operated, and the actual articles with which they carried out their duties. Garnering the information from original documents of the period, this approach tends strongly toward unfiltered realities, rather than the creation and embellishment of personal myths. It also allows the reader to take in the human sensations of the moment, as they were recorded in writings of the time: tension, excitement, apprehension, optimism, fear, disappointment, pride, remorse, contentment, scorn, sorrow, anger, elation. In contrast to overview-style history, the bumps of life of the participants are not smoothed here, the twists and turns of their careers are not straightened, and events of the time are not distilled and summarized.”

“One of the greatest strengths of the microvision approach to history is that it does not promote personal mythologies. In sharp contrast to this approach, in conventional summarized versions of history, each repetition of the names and exploits of the more prominent figures causes these individuals to loom ever larger and more mythic. Jacques Marquette, Louis Jolliet, Daniel DuLhut, Robert de La Salle, Nicolas Perrot, Pierre Gaultier de La Vérendrye, and now-famous figures were real people. They were simply ambitious, inspired individuals who worked energetically to do their jobs and achieve their goals. These were not larger-than-life individuals, living in a magical era. For example, Jean Nicolet is typically portrayed in the usual generalized histories as the brave explorer who, in 1634, was the first European to venture out on his own to the Straits of Mackinac and to Green Bay, seeking to travel through and map an uncharted wilderness. In reality, he was simply the representative of Champlain and the French population on the St. Lawrence, the interpreter and commercial ambassador who had been assigned to accompany seven Hurons who were paddling their own canoes to Green Bay. The little party traveled from the Huron villages south of Georgian Bay to the Straits and then on to Green Bay, along a common trade route with which the men were familiar. The goal of this voyage was to negotiate a peace treaty, so that commerce between the French and various of their native allies could move forward without interruption or bloodshed. No major heroics were involved, nor was any brave exploration carried out.

The goals of the present author include expanding considerably the cast of characters of the fur trade era, making known the activities of these myriad individuals, and promoting similar work by other scholars. This approach is in direct opposition to the generalizing and summarizing method, which compresses, simplifies, and reduces historical events to a select few individuals and a recitation of a limited number of their activities.”

“One of the primary reasons for including in the present study the twenty years of British occupation of Ft. Michilimackinac, from 1761 to 1781, is to clearly show that this period was, in nearly all respects, simply a continuation of the French fur trade. Until Britain suddenly acquired New France in 1760, most merchants in the British colonies bordering the Atlantic had had little or no experience in the native peltries trade. The primary exceptions were those outfitters and traders who had operated for a number of decades out of Albany. This latter community was located at the central point on the water route between New York City to the south and Ft. Oswego and the heart of Iroquois territory to the west.

Far to the north, on Hudson’s Bay and James Bay, Hudson’s Bay Company traders had remained comfortably ensconced in their bayside posts ever since 1668, supplied by ships directly from England. There along the coasts, the traders had waited for the native populations to paddle out to them with their supplies of peltries, and then paddle back to their home villages laden with newly-acquired merchandise from the traders. Only in 1743 did these company men begin to expand inland from their coastal facilities, with the initial establishment of Henley House. However, this post was located only about 150 miles inland from the shores of James Bay. The company then waited an additional 31 years before seriously embarking inland, with the creation of Cumberland House in 1774, in the area northwest of Lake Winnipeg.

When the British acquired military and political control of the St. Lawrence Valley in 1760, every aspect of the former French peltries commerce was in full readiness to resume business, which had been interrupted only during the final stage of the war. An infusion of new merchandise and supplies was the only element which was lacking. With shipments of goods from New York and New England, via Albany, and eventually directly from Britain, the commerce was immediately resumed.

In the St. Lawrence Valley, the restored fur trade involved virtually the same French seamstresses, woodworkers, metalworkers, canoe builders, provisions farmers, warehouse employees, outfitters, and other individuals who had formerly been associated with the trade, as well as many of the same former investors. Along the waterways to the west and at the communities in the interior, virtually the identical group of voyageurs, traders, interpreters, canoe builders, provisions producers, and other employees who had formerly participated in this commerce also resumed their former duties, in the business of providing articles to the same former customers. The very same water routes from the earlier days were again traveled in the identical manner as before, following the exact same seasonal schedules. The articles of merchandise and supplies were also nearly unchanged, compared to those from the French period.

However, there occurred over the following decades a gradual decrease in the number of French investors and outfitters in the St. Lawrence communities, along with a less obvious decrease in the number of French traders in the interior. This pattern was paralleled during these same years by a commensurate gradual increase of British personnel in the roles of investor, outfitter, and trader. In addition, different sources of imported articles from Europe were utilized, to equip both the French and British outfitters of the St. Lawrence Valley. These new suppliers replaced the exporters in France who had formerly been involved during the French regime.”

“Between 1669, when documented French and native presence commenced on the north side of the Straits at St. Ignace, and 1781, when the French and British residents of Ft. Michilimackinac and the adjacent community moved from the southern shore of the waterway onto Mackinac Island, a total of 112 years passed. During this period, the British were in control for only the final twenty years, from the autumn of 1761, when British troops first arrived on the scene, until the ultimate move to the Island in the autumn of 1781. Since the French fort on the southern side of the Straits was constructed in about 1715, the 92 year period of French rule of the region was split equally between the two sides of the waterway, with each half containing 46 years. The following period of British control represented a mere 18 percent of the total time span of occupation on the two shores of the Straits. Even when including the fifteen years of their tenure on Mackinac Island, which extended until 1796, the British occupied the Mackinac Straits only 28 percent of the time during the period of 1669 through 1796.

There is a very strong tendency in the United States and Canada to emphasize in our history the contributions of the British and Anglo-American populations, and to minimize those of the French people who proceeded them. The nineteenth century French historian Joseph-Ernest Renan once commented, ‘To forget, [and] to get ones’ history wrong, are essential factors in the making of a nation.’ Let us remember correctly, and get our history right, when we consider the deeds of those who came before us. ”

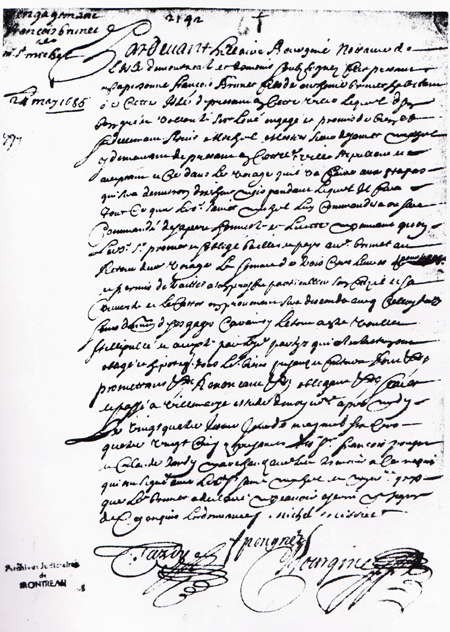

Figure 15. 1685 hiring contract of the voyageur-trader Francois Brunet dit Le Bourbonnais, who operated in the St. Ignace region during 1685-1687. After the system of trade licenses had been officially inaugurated in 1682, this document was one of the very earliest known contracts of fur trade employment to be recorded. (Courtesy of Archives Nationales du Québec)

“Before Hilaire Bourgine, notary of the Island of Montreal, and the undersigned witnesses was present in person François Brunet, son of Antoine Brunet, land-owning inhabitant of this island, at present in this city, who, of his own free will and voluntarily, has bound and engaged himself and promised to well and faithfully serve Michel Messier, Sieur de Saint Michel, residing at present in this said city, who has specified and accepted him for the voyage of about eighteen months which he is going to make to the Ottawas. During this period, [Brunet] will do all that the Sieur Saint Michel commands or will command of him which seems honest and lawful. In consideration of which, the said Sieur promises and obliges himself to give and pay to the said Brunet, upon his return from the said voyage the sum of three hundred livres for wages, and he has permission to trade, for his own profit, his gun and his blanket. The beaver pelts derived therefrom will be brought down with those of the Sieur, without any deductions from his wages.

Thus, everything having been willfully specified and agreed upon by the said parties, who have the intention of being obligated to mortgage all of their possessions, present and future, they have promised, waived, and obligated themselves.

[This agreement] made and passed at Villemarie in the office of the notary, in the afternoon of the twenty-fourth day of May, sixteen hundred eight-five, in the presence of François Pougnets and Claude Tardy, merchants of the said place, as witnesses, as required, who have signed with the said Saint Michel and the notary. The said Brunet has declared the he does not know how to write or sign, upon being questioned according to the ordinance.

Signed,

C. Tardy, F.Pougnets, Michel Messier, Bourgine”

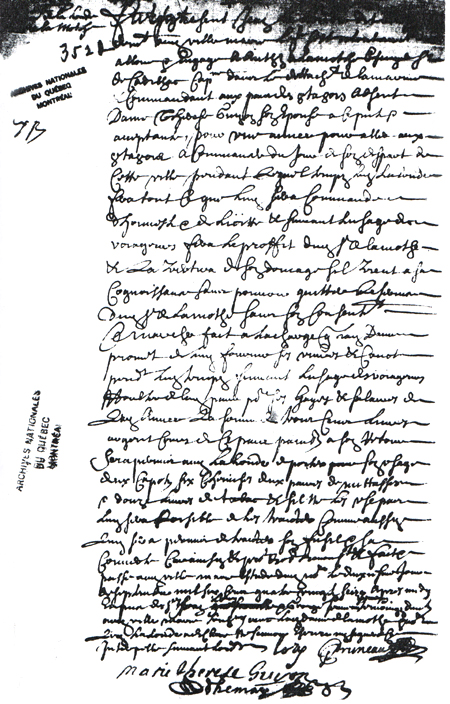

Figure 20. 1696 voyageur contract between Jean Baptiste Lalonde dit L’Espérance and Cadillac, signed at the bottom by Marie Thérèse Guyon (Madame Cadillac), two witnesses, and the notary Adhémar. Lalonde worked for Cadillac’s commercial enterprises at the Straits during the officer’s last year of command at Ft. de Buade. (Courtesy of Archives Nationales du Québec)

“Was present Jean Lalonde dit L’Espérance, residing at the said Ville Marie, who has voluntarily bound and engaged himself to Antoine de Lamothe, Esquire, Sieur de Cadillac, Captain of a detachment of the Marine Department and commandant of the region of the Ottawas, who was absent. Dame Thérèse Guyon, his wife, was present. [Lalonde] has agreed to go for one year to the Ottawas, to commence on the day of his departure from this town, during which time the said Lalonde, will do all that shall be commanded of him that is honest and lawful and according to the custom of voyageurs, for the profit of the said Sieur Lamothe, and will avert any loss for him if it comes to his knowledge. He is without the authority to leave the service of the said Sieur de Lamothe without his consent. This agreement is made with the stipulation that the said Dame [Lamothe] promises to furnish his provisions and canoe during the said time according to the custom of voyageurs, and in addition to pay as his wages and salaries for the said year the sum of three hundred livres in currency of the region, payable upon his return. The said Lalonde will be permitted to take for his own use two hooded coats, six shirts, two pairs of leggings, and twelve pounds of tobacco, and if they are not worn out, he will likewise be allowed to trade them. He will also be permitted to trade his gun and his blanket. Thus have they promised, obligated themselves, renounced, etc.

[This agreement] made and passed at the said Ville Marie in the office of the notary, the second day of September, one thousand six hundred ninety-six, in the afternoon, in the presence of Sieurs François Lory and Georges Pruneau, defense attorney for civil cases, as witnesses, residing at the said Ville Marie, who have signed below with the said Dame de Lamothe and the notary. The said Lalonde has declared that he does not know how to write or sign, upon being questioned according to the ordinance.

Signed,

Marie Therese Guyon, Lory, Pruneau,

Adhemar, notary

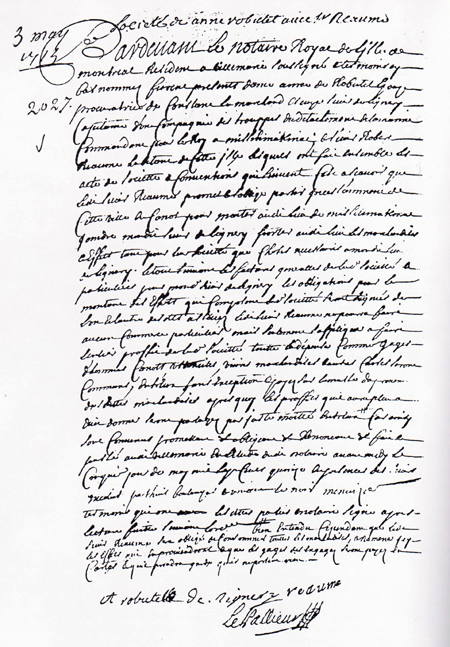

Figure 25. Partnership contract from 1715, between de Lignery, commandant of Ft. Michilimackinac, and Robert Réaume, prominent voyageur-trader. The agreement, for carrying out commerce at the Straits, was arranged in Montreal by Anne Robutel, de Lignery’s wife and legal representative in his absence, who signed the document. (Courtesy of Archives Nationales du Québec)

“Before the royal notary of the Island of Montreal, residing in Villemarie, who has signed below with the below-named witnesses, were present Dame Anne de Robutel, wife and agent of Constant le Marchand, Esquire, Sieur de Lignery, Captain of a company of troops of the detachment of the Marine Department, commandant for the King at Missilimakinac, and Sieur Robert Réaume, land-owning inhabitant of this island, who have together made these acts of partnership and agreement which follows. It is to be known that the said Sieur Réaume promises and obligates himself to leave immediately from this town with a canoe, to go up to the said place of Missilimakinac to join the said Sieur de Lignery, in order to carry to the said place the merchandise and articles which for their partnership are necessary things for the said Sieur de Ligney, all according to the general invoices of their partnership and particularly for the said Sieur de Ligney. The contracts for bringing up the articles which are charged to their partnership will be signed by both one and the other of the said associates.

The said Sieur Réaume will not be permitted to carry on any personal commerce, but will only apply himself entirely to the profits of the said partnership. All of the expenses, such as wages for the men, canoes, implements, wines, merchandise, and other things, will be mutually shared between them, without exception, and will be paid from the proceeds of the said merchandise, after which the profits which will be more than the sums paid out will be shared between them by exact halves. It is well understood, however, that the said Sieur Réaume may be obliged to use up all of the merchandise [supplies] in bringing here the articles with which he will be provided, that the wages of the hirees will be paid in card money, and that he will take care that the hirees deliver nothing [other than the cargo of the partnership]. Thus have they agreed, promised, obligated themselves, waived, etc.

[This agreement] made and passed at the said Villemarie, in the office of the said notary, in the afternoon of the fifth day of May, one thousand seven hundred fifteen, in the presence the Sieurs Nicolas Perthuis, baker, and Vincent Le Noir, joiner, as witnesses, who have signed with the said parties and the notary after the reading was done, according to the ordinance.

Signed,

A Robutel, Reaume, Le Pallieur

[and much later by] de Lignery”